By Steven Clark

Editor’s Note: Beyond the Lab Coat was a feature SBH Medicine launched several issues ago to highlight those physicians who have interesting “back stories” that go well beyond their lives as physicians. This included doctors with interests, passions and accomplishments in a variety of fields and with unique hobbies.

In this issue, we chose to return to this feature by sharing the stories of three physicians whose lives outside the hospital are well worth telling.

Neurosurgeon Who Worked on the Space Program

BEFORE HE BECAME A BRAIN SURGEON, DR. DAVID PHILLIPS WAS A ROCKET SCIENTIST.

Or, at least, a space engineer.

Dr. Phillips, a neurosurgeon at SBH, was hired by the Canadian Space Agency shortly after completing a Master of Science degree in space studies. The Toronto native served with the space agency, based in Montreal, as a robotics instructor and operations engineer. In this capacity, he instructed astronauts, cosmonauts and mission controllers on the use of the robotic systems on the exterior of the International Space Station. He and his team developed and implemented a training program that included didactic teaching, simulation and evaluations.

His job included running American, Russian, European, Japanese and Canadian astronauts through simulators that were almost exact replicas of what would be used on the space station. “My job mostly involved teaching and training,” he recalls. “We had to first learn how to use it ourselves, work with the operations team to figure out how it would be used in future missions and ensure the simulator reflected what was on the space station. Typically, we would have the astronauts come to Montreal and take them through a week course and then later do a week-long advanced course.” He and his team also took regular trips to NASA in Houston.

“Everyone was just excited about the work,” he says of the young engineers he worked with. “You’d go to work and knew it would be another cool day at the office.”

He got to know the visiting astronauts, occasionally taking them out to dinner or skiing. He remembers fondly one Canadian astronaut who was later known for singing David Bowie songs in the space station. A cosmonaut, who was also a physician, told him that the cut he suffered above his eyebrow was going to be OK because “scars are jewelry for men.”

“It was all of the interesting parts of engineering,” he says. “Problem solving, people skills, interesting technologies and how they interact with the rest of the space station. The space station was all in the process of developing and at the time we didn’t know how it would play out.”

Dr. Phillips also remembers waking up one morning and hearing about the tragic loss of the space shuttle Columbia, which in 2003 disintegrated upon reentry killing all seven crew members. Many of his colleagues supported the astronauts on that flight. “To those of us in the program, it hit very close to home.”

While working in the space program as a young man in his mid-20s, he says “medicine was in the back of my mind, but I never expected that was where my path would go.” Yet, after four years, he chose to switch careers.

“Medicine is a fascinating engineering problem as there are so many facets at play without a single optimized solution. In addition to the biology, physics and chemistry at play in the human body, interpersonal and manual skills become bigger parts of the puzzle,” he says. “With the lull in the space station program after Columbia and the impending decommissioning of the shuttle fleet, the timing for a return to school worked out.”

He believes his aerospace background has served him well as a neurosurgeon. “Being an engineer and understanding biomechanics and how we handle all the data we accumulate in the ICU and how to integrate technology has made a difference. I feel I can bring my skills to the table that others don’t have.”

Yet, he admits missing his first career. “As a resident being on call at 11 p.m. and seeing a trauma case in the ER, I would think that my old career was nothing like this. We worked long hours, but not like in residency. My Friday nights as an engineer didn’t involve breaking bad news to family members of someone in the trauma bay.

“It’s a cool part of my life that my kids ask me about. We find a mission patch or robot model and it brings back to me those warm memories.”

Dr. Phillips is often asked whether he ever got a chance to fly weightlessly in space, like astronauts did in the International Space Station (and which entrepreneurs now make available for the curious and wealthy at a cost of about $7,500 without leaving the earth).

“When I was getting my Master’s I got to go in what we colloquially called the ‘vomit comet,’ a zero gravity airplane and did a series of science experiments on the airplane,” he says. “We would have short bursts of weightlessness of about 30 seconds each where we could float or do somersaults before going into the 2G recovery part of the dive, when the airplane would turn on its engines and get a big boost into the sky and you’d get pressed into the floor of the plane.

“Even though I’ve never been to space, it was a great first career and I took away some great stories.”

A Nationally Ranked Fencer

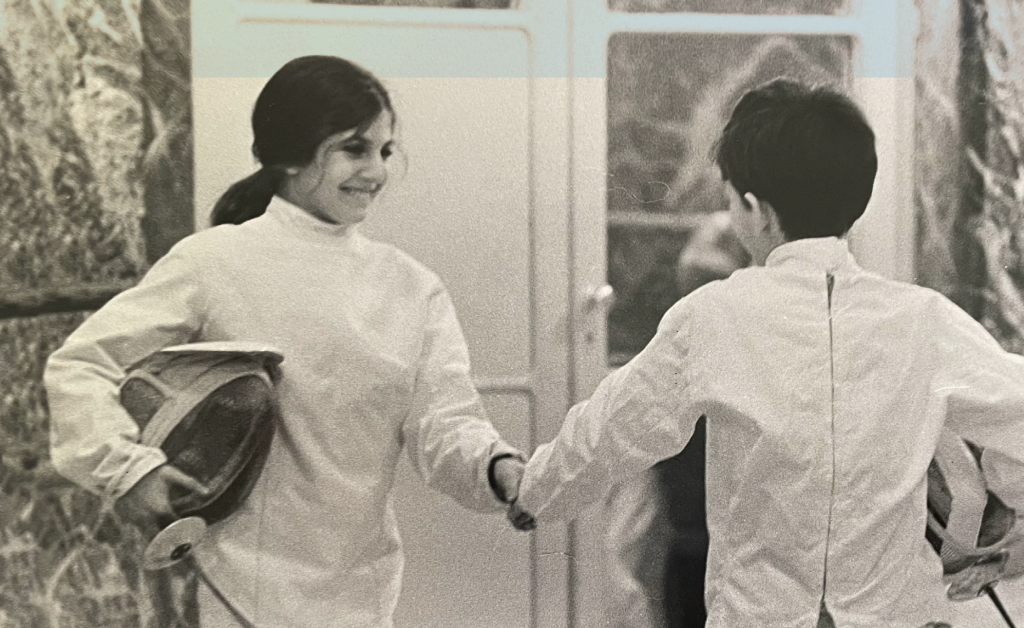

THE FALL 1995 ISSUE OF AMERICAN FENCING MAGAZINE INCLUDES ON PAGE 28 THE RESULTS FROM A RECENT TOURNAMENT, NORTH AMERICAN CIRCUIT #1, THAT TOOK PLACE IN KANSAS CITY, KANSAS. UNDER WOMEN’S SABRE, LISTED #1, IS THE NAME VICTORIA BENGUALID.

Published in the beginning of a Princeton University women’s fencing guide is a list of the recipients of the Wanda P. Sieja Award. The award is given annually to the varsity fencer who “best exemplifies good training, sportsmanship and loyalty and who through dedication and perseverance contributed outstanding service to the team.” The 1979 award recipient is the same Victoria Bengualid.

Today, Dr. Bengualid is an infectious disease specialist and the internal medicine residency program director at SBH. Ever since the birth of her second child 25 years ago, she’s put away her sabre, but has never lost her passion for a sport she started competing in “for fun” as an eight-year-old after her parents suggested that she and her younger brother could choose either fencing or judo as their after school sport.

Her brother chose judo.

Dr. Bengualid started taking the sport seriously as a teen. She qualified for and later competed in the Junior Olympics in Boston, reaching the semi-finals before, she admits, “being psyched out.” She lost the match, but learned a lesson. “I thought that I must not be good enough. I couldn’t decide whether I should eat before or after the match. I remember being very tired. From then on there was a lifestyle change. I learned that it was important as an individual to not get psyched out and believe in yourself. It made a difference in my life.”

She changed her weapon from foil to sabre, a weapon that has been traced back to the Calvary and is called the Formula 1 racing version of fencing. It requires fast, aggressive and split second decision-making, with points won or lost in a matter of seconds. At Princeton, she was co-captain of the women’s team – although, as an Orthodox Jew, she would not compete on Saturdays.

She fenced through medical school at NYU and residency and fellowship at Montefiore, becoming the first woman to train under Yury Gelman, a six-time U.S. Olympic coach. “I would leave the ICU at Montefiore after working for hours and being exhausted and then I’d practice fencing for three hours four nights a week and have all the energy in the world.”

Dr. Bengualid continued to compete and do well on a national level well into her 30s, while working as an attending at St. Barnabas Hospital. She would occasionally beat the top 10 male fencers. Yet, once she got married and had kids, she found it wasn’t the same – “I wanted to be home with my kids and I was frustrated that I could no longer put in the time needed.”

It’s a sport, she says, that is both physically and mentally grueling, requiring regular practice sessions to practice the necessary footwork and a training regime that included doing 100 lunges daily.

She remains, however, passionate about the sport. She keeps tabs on youngsters in her synagogue who fence and does some coaching. She says she misses the “thinking process, physicality and camaraderie of the sport. It’s like a chess match where you have to figure out the person in front of you, how they move, how they react.”

Call Me Sergeant

WHEN DR. JAY LEKIREDDY, A SOFT-SPOKEN MAN WITH AN INDIAN TILT TO HIS VOICE, TELLS PEOPLE THAT HE SERVED IN THE U.S. MILITARY, HE GETS STRANGE LOOKS. PEOPLE ROLL THEIR EYES. LOOK AT HIM WITH DISBELIEF. THEY THINK HE’S PULLING THEIR LEG.

“No one believes me,” he says. “It’s hard to see an Indian in the U.S. Army.”

Dr. Lekireddy, a fourth-year psychiatry resident, is one of a number of people at SBH to have served in the U.S. military. Yet, he is likely the only one to have enlisted in the U.S. Army just four years after coming to the United States from Hyderabad in the southern part of India.

It was 2009, and he had recently moved from New York City to Washington State. He was in the U.S. on a student visa and studying for his USMLE exams. His plans, should he get accepted into a residency program in the U.S., was to specialize in internal medicine.

This was when a friend suggested he enlist in the military.

“A lot of Indian people questioned why I would want to join the U.S. Army,” says Dr. Lekireddy, while sitting in a small office inside the inpatient psychiatric ward in Kane 3. “But, I thought it would be an interesting experience.”

By joining the army, he was able to become a U.S. citizen. He served from 2009 – 13, stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington with the 1st Special Forces Airborne. He trained as a paratrooper and did 16 jumps from a C17 aircraft, including a Chinook helicopter.

Due to his language proficiency, he was selected for Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET), a training exercise with Indian special operation forces. JCET was a bilateral joint exercise whose mission was to improve the ability of the forces in the two armies to respond to a wide range of military contingencies.

“I helped to bridge the language and cultural gap between the two forces,” he says. Twice the Army deployed him to India and once Indian forces came to the U.S. to train with him and his unit.

During this time, he witnessed fellow soldiers suffering from PTSD, depression, Bipolar Disorder and other mental illnesses. It affected him and he soon saw that he could help them. More so, it gave him a more defined career outlook: he wanted to work, he realized, with military veterans suffering from mental health issues.

In retrospect, he says, his four years in the army gave him confidence and focus. In 2018, the army sergeant was accepted into the St. Barnabas psychiatry residency program. Today, six months away from graduation, Dr. Lekireddy has short and long-term plans. He hopes to stay at St. Barnabas and work as an attending psychiatrist. In the not-too-distant future, his goal is to work with the Department of Veteran Affairs as a psychiatrist.

“I’m very proud of having served in the army,” he says. “Looking back, it certainly made a difference in my life.”